En Mars 2021, le délai de clémence de la CNIL a touché à sa fin. C’était le délai accordé par la Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés pour que les entreprises puissent mettre en conformité leurs outils digitaux et leur écosystème selon les recommandations du Règlement Général sur la Protection des Données à propos des cookies. Depuis, les premières amendes relatives au non-respect du RGPD ont été distribuées…

Respectez-vous les règles de consentement sur votre site internet ? iubenda, solution de conformité en ligne, et Codeur.com vous présentent 8 erreurs courantes à éviter pour être en conformité avec la règlementation.

Le RGPD, un imbroglio juridique aux expertises nouvelles

Le RGPD demande de nouvelles compétences, à mi-chemin entre l’expertise juridique et l’expertise digitale (notamment en termes de collecte du consentement et interactions des applicatifs de l’écosystème digital). À cette issue, un nouveau métier a fait son apparition : le DPO, Data Protection Officer.

En effet, les entreprises ont besoin d’être guidées et conseillées, dans un environnement juridique où les lignes directrices évoluent constamment – aussi régulièrement que les avancées techniques font leur apparition !

Mais, comment maintenir son écosystème digital, et principalement la vitrine de son site web, à jour avec les directives de la CNIL, sans que cela devienne chronophage pour l’organisation ?

Les solutions comme iubenda proposent une option alternative : elles ne remplacent pas le fait d’avoir un DPO (dont le champ d’expertise s’étend au-delà de l’écosystème digital – notamment en prenant en compte les responsabilités RH, comptables, commerciales) mais apportent un solide gain de temps à la mise en conformité de votre site web.

À lire aussi : Google Analytics et RGPD : êtes-vous en conformité ?

Votre site web, la première vitrine de votre entreprise pour la CNIL

Pourquoi est-ce si important d’avoir un site web conforme au RGPD ? Il existe trois raisons principales :

- Une défiance des internautes, s’ils remarquent que vous ne respectez pas les règles de collecte du consentement

- Un risque de délation de la part de vos concurrents, qui peuvent vous reporter à la CNIL si votre bandeau cookie ne semble pas conforme

- Un contrôle potentiel de la CNIL, si elle tombe sur votre site internet non conforme, avec un risque d’amende à la clé

Tous ces risques représentent une perte de temps, d’argent et de crédibilité : un vrai fardeau pour l’entreprise !

Les solutions comme iubenda vous permettent de reprendre le contrôle facilement de la mise en conformité RGPD de votre site.

Qu’appelle-t-on un bandeau cookie ? C’est une bannière s’affichant à la première visite du site qui informe l’utilisateur de l’usage de cookies et demande son consentement.

8 erreurs de conformité évitées par les solutions RGPD tout-en-un

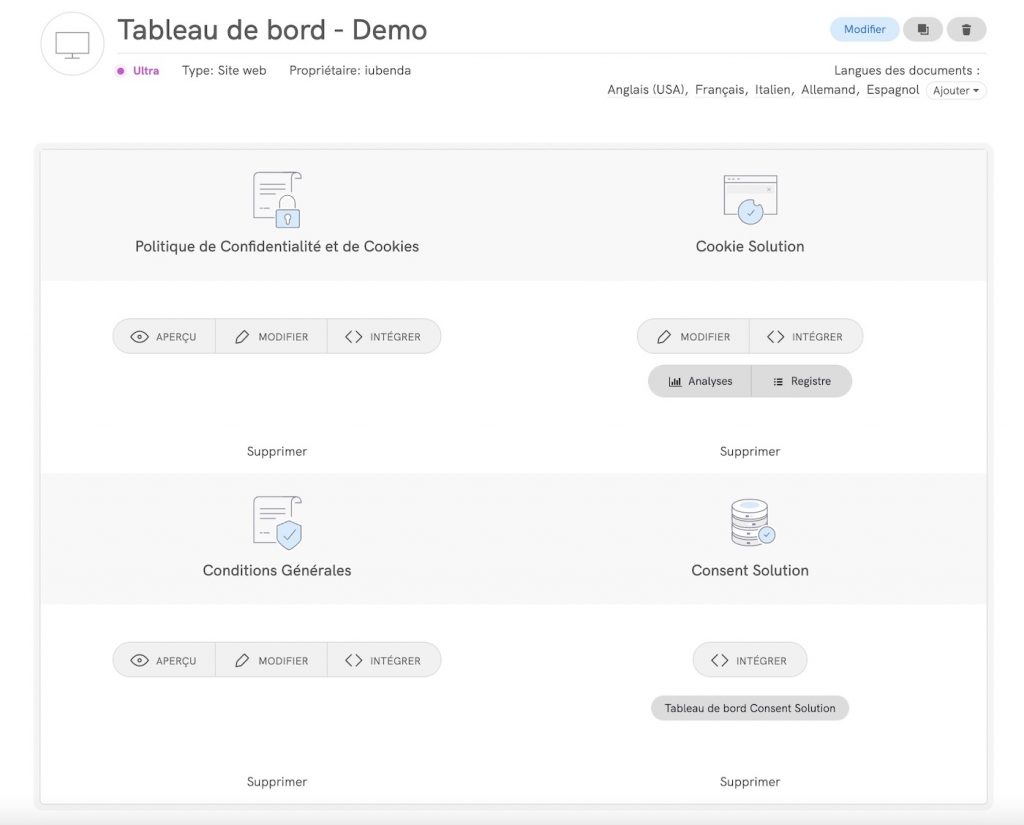

Grâce à iubenda, vous possédez une solution à 360° pour gérer en quelques clics la mise en conformité de vos sites web et applications.

Cette solution vous permettra d’éviter, sans effort, les 8 erreurs de conformité les plus communes :

Erreur #1 : Une documentation RGPD qui n’est pas à jour

Grâce aux solutions RGPD, vous n’avez pas besoin d’internaliser de temps de veille pour suivre toutes les évolutions de la CNIL, vous tenir à jour sur les nouvelles normes de bandeaux ou règles de collecte de consentement aux cookies.

L’équipe de iubenda le fait pour vous et fait évoluer l’outil au fur et à mesure des recommandations de la CNIL et évolutions des autres législations internationales.

Erreur #2 : Ne pas adapter son bandeau cookie à la typologie d’utilisateur (pays/langue)

Le RGPD, comme son nom l’indique, s’applique aux internautes Européens. Toutefois, en plus de l’Europe, il existe d’autres États aux règles adéquates (comme le Brésil ou la Californie), qui nécessitent également un suivi des règles de consentement.

C’est donc tout un travail d’adapter les documents et les bandeaux à la réglementation et langue d’un pays. Mais un travail largement facilité par iubenda, grâce à la fonction de géolocalisation de l’utilisateur.

Découvrez quelles lois s’appliquent à votre site grâce au quiz : “Quelles lois s’appliquent à vous et votre société ?” (1 min)

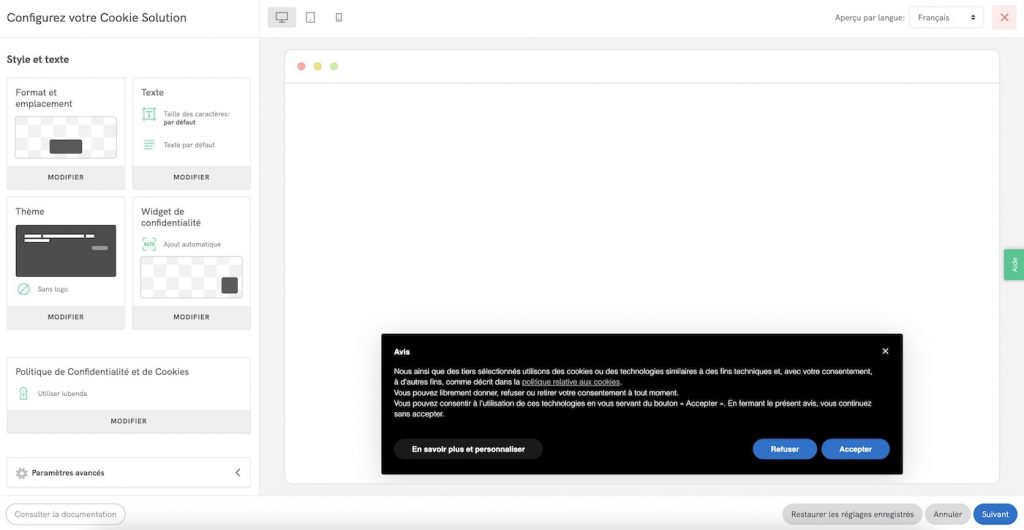

Erreur #3 : Une mauvaise configuration de votre bandeau cookie

Les solutions tout-en-un sont pensées pour démocratiser et faciliter l’application du RGPD aux sites web.

Si la solution est conçue pour s’intégrer facilement sur les sites web pré-packagés, type Prestashop ou WordPress, il ne suffit pas d’installer un bandeau cookie pour qu’il soit configuré !

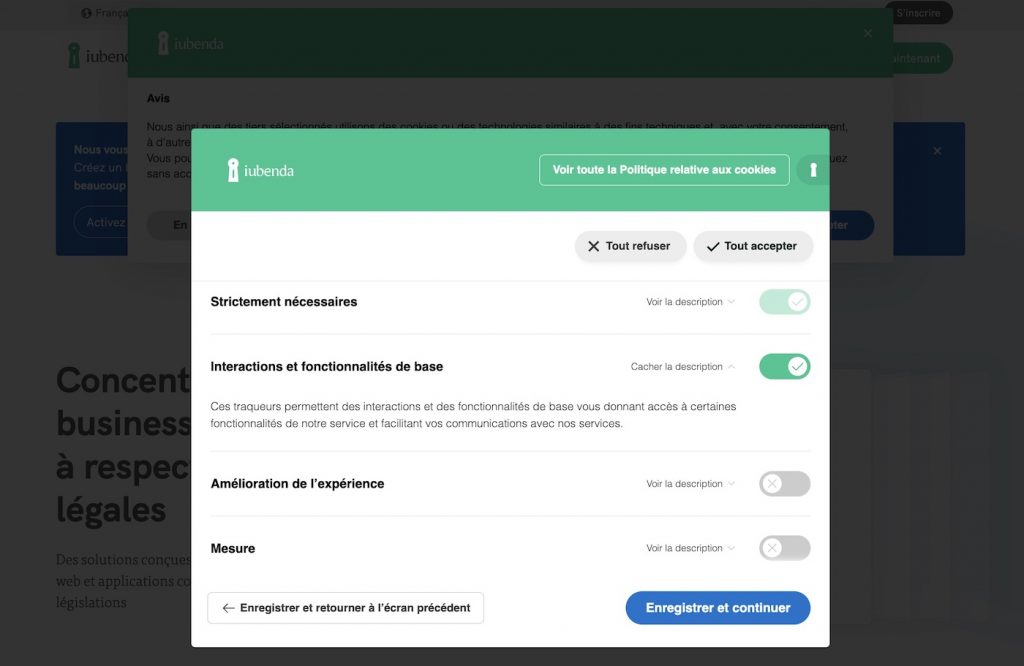

Par exemple, en France, il ne vous faudra pas oublier les éléments suivants sur votre bandeau cookie :

- deux boutons « Accepter » et « Refuser », au même niveau et avec la même visibilité

- un bouton « En savoir plus et personnaliser » pour donner plus d’infos sur les cookies et permettre de personnaliser plus en détail les préférences de consentement

Souvent oubliés, ces boutons sont indispensables pour respecter la législation applicable en France. C’est pourquoi ils sont mis en place automatiquement lors de la configuration par la Cookie Solution iubenda.

Erreur #4 : Ne pas conserver ses preuves de consentement utilisateur

La CNIL recommande l’utilisation d’outils comme les Consent Management Platforms (CMP) pour collecter et conserver une preuve du consentement aux cookies. Sans l’aide d’une telle plateforme, c’est très technique à mettre en place.

iubenda est une CMP certifiée. La plateforme crée ainsi automatiquement un registre des consentements pour conserver une preuve des préférences de consentement sur les cookies exprimées par chaque utilisateur lors de leur visite sur le site web (ce sur quoi ils ont cliqué lors de l’affichage du bandeau cookie). Le registre est accessible depuis le tableau de bord iubenda.

Ce registre est nécessaire pour votre documentation RGPD !

Erreur #5 : Négliger de lister certains outils de suivi des utilisateurs

Vos différents outils de suivi, outils d’analyse type Google Analytics, les boutons vers les réseaux sociaux doivent être listés dans la politique de confidentialité.

La notion d’informer les utilisateurs de façon compréhensible est très importante aux yeux du RPGD. Dans ce souci de clarté, iubenda génère les documents juridiques en version simplifiée (disponible bien sûr en version complète aussi).

Erreur #6 : Oublier l’accessibilité

La CNIL stipule que l’information relative aux cookies doit être :

- facile d’accès,

- concise,

- fournie de manière claire et compréhensible.

Veillez donc à respecter les règles d’accessibilité lors de la création de votre bandeau cookie : contraste de couleurs élevé, police de caractère lisible, de taille raisonnable…

Cela ne vous empêche pas de personnaliser votre bandeau cookie ! N’hésitez pas à reprendre les codes de votre charte graphique, pour intégrer au mieux le bandeau cookie sur votre site.

Erreur #7 : Ne pas lister les cookies présents sur vos sites

Pour cela, vous pouvez informer vos utilisateurs des cookies utilisés grâce à une politique relative aux cookies, qui va souvent de pair avec la politique de confidentialité.

Cette politique de cookies doit être accessible depuis le bandeau cookie.

La mention de l’ensemble des cookies et de leur utilité est obligatoire.

Erreur #8 : Ne pas mettre en ligne votre documentation RGPD

Il existe une documentation RGPD obligatoire pour votre site web.

Cette documentation commence par votre page de politique de confidentialité, qui résume les droits des internautes, les modalités de contact de votre entreprise en cas de réclamations RGPD, mais également ce que vous faites avec les données à caractère personnel de l’internaute et à quelles fins.

Grâce à iubenda, vous obtenez une page de politique de confidentialité complète, automatisée, en un clic ! La solution permet également d’intégrer facilement ce document sur votre site web, par exemple dans le footer. De cette manière, votre politique de confidentialité est accessible depuis chaque page du site (recommandé).

À retenir

Pour être en conformité avec le RGPD, il ne suffit pas d’ajouter un simple bandeau signalant la présence de cookies. Évitez les 8 erreurs citées ci-dessus pour améliorer votre suivi des leads tout en respectant la règlementation.

Les solutions tout-en-un type iubenda facilitent votre travail en permettant, simplement et respectueusement des règles RGPD, de garder la main sur votre site web et de mettre le curseur Marketing-RGPD au meilleur endroit pour vous.

⚡ OFFRE SPÉCIALE : Bénéficiez de -10% sur votre premier achat iubenda depuis cet article !